Mirko Tobias Schäfer / Assistant Professor

University of Utrecht Department for Media and Culture Studies

Mirko Tobias Schäfer / Assistant Professor

University of Utrecht Department for Media and Culture Studies

The mainstream media are now covering 3D printing and the so-called maker revolution. This popular discourse nourishes a legend of a new industrial revolution where everything can be easily reproduced through 3D printers. The Economist featured a printed Stradivarius and told the story of a future where 3D printing would revolutionize not only the manufacturing industry but also open the opportunity to reproduce rare artifacts. Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen indicate in their book The New Digital Age, that 3D printers will allow us to preserve our cultural heritage by simply replacing lost or destroyed artifacts with 3D prints. That way, they argue we can simply restore the loss of any objects of cultural value, as for instance the Buddhas of Bamiyan which were destroyed by the Taliban in an act of iconoclastic vandalism. Those accounts speak of the overly positive framing of 3D printing as a new and revolutionary technology. Neither 3D printing nor the superficial techno-enthusiasm are new. The first 3D printer has been developed by Chuck Hall in 1984 and since then 3D printing has been used in industrial design for prototyping. The enthusiasm displayed in the examples accompanies technological innovation and shapes popular misconceptions as long as media publish stories about technological advancement.

However, there is -quite rightly- awareness for 3D printing. Decreasing prices, easy to use devices and an abundance of freely accessible blueprints and tools for editing allow even novice users to become makers. What has been first a technology of industrial design and became then a technology of enthusiast hobbyists, hackers and makers is now available for broader audiences. This will surely open a world of new possibilities, entrepreneurial success stories and fascinating examples of user creativity. Therefore it is an applaudable effort of SETUP Utrecht to provide an exhibition that does not only present these media practices in action but also provides the opportunity to reflect on opportunities and challenges of the future maker culture.

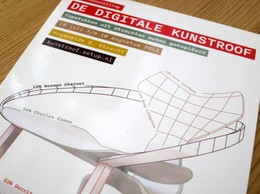

As the title Digital Art Robbery indicates, 3D printing might very well open a new chapter in the history of copyright wars. It exceeds by far the problematic of common digital culture where unlicensed copies of video, images, text and music violate copyrights. The problem of digitized texts which affected largely the media industries will now be a problem of digitized artifacts and affect industrial design and engineering and the large industry of merchandising goods. The exhibition features a mash-up design chair, which perfectly illustrates the problematic we have to deal with. This chair combines various design components from classics in furniture design such as Charles Eames, Gerrit Rietveld, Arne Jacobsen and others.

While 3D printing professionalizes it turns former pioneers such as MakerBot Industries into market leaders and affects their understanding of the merging media practice. The decision to move away from an open source to a proprietary model received criticism from the maker scene. Critics were concerned to what extend MakerBot would coerce control on the printing device and the blueprints. And indeed MakerBot made another unpopular move when censoring their popular platform for 3D blueprint sharing Thingiverse by removing the controversial designs of a handgun and other weapon accessories. The response was the alternative platform Defcad (screenshot) which hosted the censored designs. The so-called Liberator, the 3D printed gun that made mainstream media headlines and which is exhibited here as well, demonstrates vividly the superficial quality of popular discourse which oscillates in general between enthusiastic excitement and unsubstantiated panic. Those who predicted a mass arming with printed guns, conveniently forgot that the common material for home 3D printing is plastic. As its quality to melt is a handy aspect for the process of printing, it comes in inconvenient for firing.

3D printers already are and increasingly will become essential tools in the workshops of an expert culture that uses a wide range of open source hardware. It is perfectly plausible to see local craftsmanship develop through 3D printing, providing services of producing all kinds of artifacts that are otherwise unavailable or too costly to order. Those are the makers. Next to it, on much larger scale, we will see home 3D printing as a means to manufacture the shapes developed by media industries. They will provide even easier to use means of sharing, downloading and printing shapes. Many designs will be protected by patents and copyrights and the 3D printer will blend into the advertiser friendly culture of mainstream media merchandising products. We will see great efforts by the corporate world to control the use of printing devices and the process of production as far as possible.

The decisive quality of the new wave of home 3D printing is its extension of the intangible digital realm into the world of tangible objects. It will surely stimulate a wave of creative production where expert communities of makers and tinkerers create new devices, objects and will consequently expand and professionalize the development of further means of production. 3D printing does not stand on its own, it integrates into a world of tinkering where many open source hardware devices can be combined and the hobbyists workshop will now see a fantastic upgrade in machinery. The combination of skills, accessible information networks and affordable technology has provided us with an unprecedented wave of ingenuity and innovation in the 1990s. It became obvious that innovation and technological development is not the exclusive realm of industrial research or corporate product development but happens also in the creative production communities of amateurs, hobbyists, hackers and artists. Innovation emerges also from the fringes and in the periphery of the established production channels, it emerges from the hacker spaces, the fablabs, informal workspaces and gatherings of hobbyists and tinkerers. Unfortunately Dutch policy makers have cut down funding for those fringe spaces of unexpected technological innovation and believe strongly in a top-down management of innovation. Hopefully this exhibition will also contribute to a process of revisiting this flawed understanding of innovation.

This exhibition does not only show the public how 3D printing looks like, how well and how poorly it works, but it also stimulates to think about the questions that should be asked about maker culture and the issue that need to be raised in an informed discussion. We should neither hastily buy into the enthusiast story of a rosy future of 3D printing nor into the alleged danger of printed guns. Both stories distort the real issues we need to address when speaking about maker culture.

Date August 2013 Category News

The Utrecht based media lab SETUP Utrecht put together a special exhibition featuring the qualities of 3D printing. In collaboration with Utrecht musea makers were invited to 'steal' exhibits by scanning them and reproducing them on a 3D printer. The show is called Digital Art Robbery. I had the pleasure of opening the exhibition with some remarks on 3D printing.